“How can anyone feel so important when we know that death is stalking us?”

“Death is our eternal companion […] It is always to our left, at an arm’s length.”

– Carlos Castaneda, Journey to Ixtlan

1. Of “Death is a Spiral” and Luigi Russolo

Like “Dauði Baldrs ins Góða”, the short piece of music “Death is a Spiral” was commissioned by a radio station and based on the famed theme of the third movement titled Marche funèbre of the Piano Sonata No. 2 by the Romantic-era composer and pianist Frédéric Chopin. This time, the theme instead of being in service of funeral doom was treated in a martial industrial way, inspired by Laibach and ideas from the Italian Futurist painter and composer Luigi Russolo, author of the 1913 manifesto L’Arte dei Rumori (The Art of Noises) and greatly interested in spirituality and occult arts too. Although he was certainly one of the precursors of noise music, referring to his pieces as “spirals of noises”, and considered that sounds – including those of war – from the modern era among others are able to produce pleasing sensations, his approach can not be reduced to a simple, materialistic exaltation of the machine in phase with the ideology of linear progress.

On the contrary, Russolo’s attempt was to create an art that would dare to dig into the essence of things and reach their deepest spiritual level; ultimately, music rather than having a solely descriptive or banally documentary function would have to spiritualize its matter and sanctifying the noise: “Music must move away from an abstract indefinite, which is the characteristic of its language, and of the matter that it uses, to arrive at a spiritual infinite.”[1] Luciano Chessa notes in Luigi Russolo, Futurist: Noise, Visual Arts, and the Occult: “At its core, the art of noises was for Luigi Russolo a process of conjuring the spirits, a process he divided into two parallel moments: one in which noise became spiritualized, the other in which spirits materialized.” An extract from a poem titled Russolo originally in French by another Futurist, Paolo Buzzi, could confirm Chessa’s statement:

Luigi, the ululatore [“howler”] is the oracle

Of the god who inspires you and who will render you justice.

The abyss, our illustrious Relative, is grateful to you.

I hear the only true musics: those

That the dead hear,

Over their heads, under our feet.

The future City awakens

In an explosion that invites

The cemeteries to masked balls of power and desire![2]

2. Of the Aztecs, their worldview, and their post-mortem abodes compared to the Norse ones

The music video uses mainly pictures related to the Aztec[3] tradition and scenes from the Mexican

horror film The Robot vs The Aztec Mummy (originally La Momia Azteca contra el Robot Humano),

directed by Rafael Portillo and released in 1958. This low-budget movie was the

last part of a trilogy, and if the scenes with actors playing Aztec people were

surely not a prime example of accurate historical reconstruction, their sombre

atmosphere and the hieratic attitude of the officiants can serve very well the

Idea of the song. The Mesoamerican traditions, more particularly the Aztec one,

had a keen awareness of death and annihilation, knowing the transiency of life

and the fact that at any time man facing a pitiless universe can be crushed by

events which are beyond his control. As recalled by Nezahualcoyōtl, the great

poet, philosopher and ruler of the city-state of Texcoco, close to the Aztec

capital Mēxihco-Tenōchtitlan:

Oh, Lords,

We are mortal,

Our mortality defines us.

We all have to die,

We all have to go away,

Four by four,

all of us.

Like a painting,

We gradually fade.[4]

But it was an active pessimism rooted in an agonistic worldview, noting that universe is a place where destruction inevitably follows creation in an interdependent way. The subsistence of the world is precarious, and possible only if the gods, who had created men and shaped the world, receive the crucial energy required to continue their fight against entropic forces in order to postpone the predictable disaster, notably through the “precious water”, namely blood from autosacrifice, highly ritualistic wars (xōchiyāōyōtl, “flowery war”) and human sacrifice, a sacred debt payment to the gods. As Jacques Soustelle writes in The Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest: “Human sacrifice was an alchemy by which life was made out of death; and the gods themselves had given the example on the first day of creation. As for man, his very first duty was to provide nourishment […] ʽfor our mother and our father, the earth and the sunʼ. […] Nothing was born, nothing would endure, except by the blood of sacrifice.”

Despite the impressive achievements of the Aztec Empire of Mexico and other Mesoamerican civilizations, human sacrifice is undoubtedly the most incomprehensible part of their Weltanschauung for Christians and modernity, which in their view could only be the act of demons worshippers, barbarians, superstition, or imperialism. Every culture possesses its own notion of what is cruel or not; if we look at the numerous crimes of Christianity and other Abrahamic religions committed in the name of “the one, true faith” or those of the modern world, including its pure atheistic or so-called humanist forms, they do not reflect a more compassionate attitude or superior moral standards… Aztecs were horrified by the atrocities such as massacres, mutilations, tortures perpetrated by conquistadores, and the very idea of “total war” was alien to their culture.

In our view, modern man has in most cases a very limited perception of his environment, both physical and subtle, and ignores the fact that landscapes are also inhabited by spirits. To make possible a human settlement without too much trouble, it may be necessary to offer compensation to placate the spirits of a place. During a travel in Mexico, we had thus to deal with inorganic beings strongly attracted by fresh blood. It is worth noting also that some academics and indigenous movements deny the existence of human sacrifice or at least their extent.[5] Furthermore, it is important to understand that sacrificial death was honourable and even desirable, an opportunity to gain immortal glory and a post mortem fate far more interesting than the common one, so much so that some of the sacrificial victims indignantly rejected the offer of release and the possibility to live with great riches, and demanded to be sacrificed.

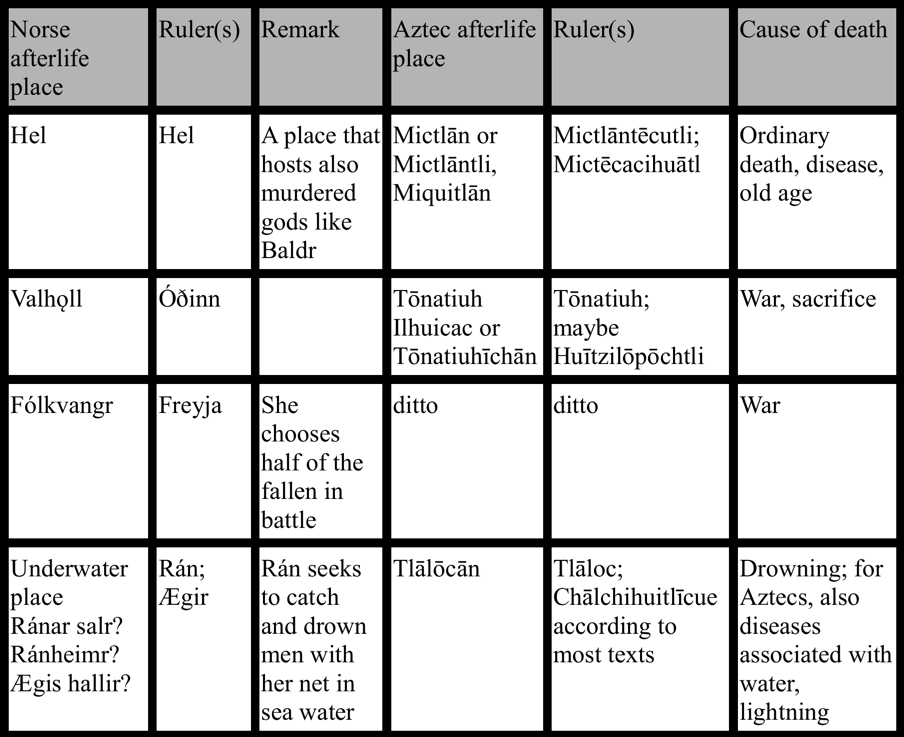

Because for the Aztec tradition like for the Norse one, the form of death was the deciding factor determining the dwelling-place where people could go to in the afterlife. Thus if we make a non-exhaustive comparison table showing some of the post mortem destinations, knowing that there was no formal doctrine in both traditions and that our understanding is still limited:

The table is in no way complete, as there are alternative possibilities proper to each tradition: for one, Aztec women who died in childbirth also joined the house of the sun and underwent transformation into “divine women” (Cihuātēteoh), and so on. We note that for the Aztec and Norse warrior, the most desirable fate was to become cuāuhtēcatl “companion of the eagle” to accompany Tōnatiuh, the sun deity, and einheri, “the one who fights alone” or “the one who belongs to an army”, to dwell with Óðinn. But the usual afterlife abode for people who died of old age or disease was Mictlān and Hel, after a journey. Both chthonic worlds are mistily situated in the north[6] and are conceived as rather gloomy, cold places. Rulers of the Aztec Hades are Mictlāntēcutli, “Lord of the place of the dead”, and Mictēcacihuātl, also named Mictlāncihuātl “Woman [Lady] of the place of the dead”, whilst Hel, the Norse underworld realm, is run by the eponymous feminine entity, whose name is ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *kel-, “to cover, conceal”.

Despite the yoke of the prominent materialistic ideologies, modern-day Mexico still considers that death and life are closely related, death being a natural part of the human cycle, and has maintained a reverence towards dead with holidays such as Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead), where the deceased are celebrated and receive offerings. The assertion, that it is in fact a recent creation of nationalistic or Christian origin instead of a resurgence of pre-Hispanic traditions rooted in Aztec festivities in honour of the goddess Mictēcacihuātl, is irrelevant for our purpose: the most essential point is that it is a living veneration of the ancestors and dead.

3. Of the unofficial folk saint Santa Muerte

In Mexico today, life presents many chaotic and threatening elements. For people – as in other countries too – in the margins of conventional society, utilitarian magic and devotion can be the sole way to get some help in difficult life situations, a kind of last resort. Whence the growing worship of the unofficial folk saint Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte (“Our Lady of Holy Death”), also known as “the Skinny Lady”, “the Bony Lady”, “the White Girl”, “the Powerful Lady”, “Lady of Shadows”, “Black Lady”, to name a few of her alternate names. A quotation from a devotee renders very well her mighty status and that in a crisis situation, she can be the last reliable ally: “I don’t know if God exists, but death yes… Death is stronger than life, as she puts an end to it. In view of a lack of meaning of life, there is an excess of meaning of death.”[7]

Although Santa Muerte genre is ambiguous, she is mostly depicted as a female skeletal figure that owes much to the mediaeval European Grim Reaper and representations of death like the Danse Macabre. But her syncretic cult, in addition to Catholicism, may have been possibly influenced by folk Afro-Caribbean traditions and may constitute a reminiscence of the Aztec netherworld deities Mictlāntēcutli and Mictēcacihuātl. Santa Muerte is sometimes shown with an owl, a nocturnal bird who was considered a messenger of Mictlān’s rulers, connected with the underworld. Veneration of death and skulls was common in ancient Mexico, as evidenced by tzompantli, an Aztec ceremonial rack of skulls. Because of the risks of persecution involved, it may be necessary to disguise pagan practices and deities behind Christian rags. Needless to say, Santísima Muerte cult, which also attracts social outcasts or people who deal with despised or dangerous activities (criminals, prostitutes, policemen…), transgression and transitions, is frowned upon by authorities, media and the Catholic Church, that declared that veneration of Santa Muerte is not consistent with Catholic teaching, blasphemous, and is tantamount of Satanism. The president of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Culture, Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, stated that Santa Muerte worship was a “degeneration of religion”. Some of her followers have even been stigmatized as “narco-satanic”.

The Norse deity Hel, sometimes anglicised as Hela, may have today a liminal role similar to Santa Muerte in some groups composed of marginal parts of the heathen demography.

4. Of Carlos Castaneda and some notions presented in his books

Last element related to “Death is a Spiral” and Mexico which will be briefly discussed here is the work of Carlos Castaneda. We are well aware that there is a lot of controversy about the veracity of the Castanedian corpus and the personality of its author, but in our case we are not interested in the question of factual authenticity or to know if he was influenced by phenomenology, Aldous Huxley, or the Mādhyamaka school of Buddhism rather than by indigenous lore. The worldview and techniques contained in his books are eminently subversive for the confined world created by the dictatorship of reason, which was able to reduce the unfathomable mystery of the universe to a “manageable nonsense”. Therefore, it is not surprising that some people have exerted much effort to debunk Castaneda’s accounts, pointing up his narrative incoherences, and thus, in the end, trying to rend them insignificant for those who are prisoners of the “superstition of facts”. Castaneda himself writes in the prologue to The Eagle’s Gift: “I am very far away from my point of origin as an average Western man or as an anthropologist, and I must first of all reiterate that this is not a work of fiction. What I am describing is alien to us; therefore, it seems unreal.”

Whether or not it was a forgery, his self-sufficient work is definitively a gateway to nonordinary reality and the testimony of someone who has seen. As previously said in a note in our short essay about Julius Evola’s book Ride the Tiger, the “differentiated man” and our song “Der Ritt auf dem Tiger”, don Juan Matus, Castaneda’s chief spiritual mentor, “may not be an organic being but an inorganic one from nonordinary reality, or Casteneda’s didactic creation to explain his own experiences and philosophy, a Platonic noble lie; what really matters for a differentiated man is the practical value of Castaneda’s teachings and terminology.”

Philosophy (“love of knowledge”, “pursuit of wisdom”) for us must obviously not be understood as an individual speculative though or an useless knowledge of facts, gathering of information, but rather as an operative gnosis, whose the higher purpose is ultimately to recover our original nature identical to the Absolute (the spiritual liberation), beyond the superimpositions and ignorance hiding it, or at least to attempt it. The great metaphysicist and Indian’s art philosopher Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy recalls in his essay On the Indian and Traditional Psychology, or Rather Pneumatology[8] that “the traditional psychology is not, in fact, based on observation; it is a science of subjective experience. Its truth is not of the kind that is susceptible of statistical demonstration; it is one that can only be verified by the expert contemplative. In other words, its truth can only be verified by those who adopt the procedure prescribed by its proponents, and that is called a ʽWayʼ. In this respect it resembles the truth of facts, but with this difference, that the Way must be followed by every individual for himself; there can be no public ʽproofʼ. By verification, we mean, of course, an ascertainment and experience, and not such a persuasion as may result from a merely logical understanding.”

Knowing that it is impossible to summarize in some lines an intricate, deep work like that of Castaneda, we will only examine a few points relevant to the differentiated man defined in Evola’s book Ride the Tiger, a rare type of man still able to carry out a spiritual quest despite the very negative conditions of the modern world and of Kali-Yuga, the Dark Age. The core idea behind the differentiated man is borrowed from Left-Hand Tantrism, and in our opinion the Castanedian way has also a “sinister” dimension, in the sense of “on the left side” based on the Latin etymology of the word, as some practices and doctrinal elements may sound really disturbing, absurd, dangerous – that is indeed the case – or “evil” for someone more accustomed to a sattvic, dexter religious view and methods.

We note first the important notion of power, to be understood not in the sense of social dominion, but as a sacred, magical and impersonal force, which can be gained or lost by acts and may be found to varying degrees in nature, places, entities, living beings, objects, and so forth. It is a mystery outside the reach of reason, which cannot be logically inferred but possibly perceived as a feeling or vibration, and stored. As don Juan puts it in Journey to Ixtlan, “a man is only the sum of his personal power, and that sum determines how he lives and how he dies.” At birth, each one receives a certain amount of personal power, from small to enormous, which is contingent among other things on his ancestors. If our starting capital does not depend on our will, we have however the choice to dissipate or increase it, bearing in mind that “if we don’t have enough personal power, the most magnificent piece of wisdom can be revealed to us and that revelation won’t make a damn bit of difference” (Tales of Power).

Seeing the world as power is an approach which is to be found in several traditions like North Amerindian and Polynesian ones, but also in Tantrism, the “fifth Veda” adapted to our current era, and in the Śāktaḥ branch of Hinduism, which unlike the Vedantic viewpoint emphasize śakti “power, energy”, the feminine kinetic aspect of the Absolute (Brahman) regarded as the divine biunity Śiva/Śakti. Sometimes a fierce goddess like Kālī is even portrayed as the supreme principle of the universe, identified with the Brahman. A Tantra states about Śakti: “Thou art all power. It is by Thy power that we are powerful.” Another text adds: “Śakti is the root of every finite existence. The worlds are Her manifestation; She supports them and one day they will be reabsorbed into Her… She is the supreme Brahman (Parabrahman)… She is the mother of all the gods; without Śakti they would cease to exist.” There is a play of words saying that “Śiva without the ʽiʼ of Śakti (power) is but an empty corpse (śava)”. For adepts of Tantrism, only practices based on śakti are efficacious in our age and a Tantric commentator has two significant remarks, which could be have made by don Juan: “things are power” and “the power of a thing does not wait for intellectual recognition”.[9]

The cosmogony exposed in the Castanedian corpus, in particular in The Fire from Within and The Eagle’s Gift, is neither creationism nor materialism but rather emanationism, all things being emanations of the first principle seen as “an indescribable force which is the source of all sentient beings” and worlds. It is called “the Eagle, not because it is an eagle or has anything to do with an eagle, but because it appears to the seer as an immeasurable jet-black eagle, standing erect as an eagle stands, its height reaching to infinity.” The old seers found also that “The Eagle creates sentient beings so that they will live and enrich the awareness it gives them with life. They also saw that it is the Eagle who devours that same enriched awareness after making sentient beings relinquish it at the moment of death”, as awareness is the Eagle’s food. The human part of the Eagle is too insignificant to be sensitive to prayers, but he has granted a gift to all living beings: the possibility to keep the flame of awareness and “to seek an opening to freedom and to go through it”.

Compared to the Eagle, the hypercosmic ruler, the most tyrannical men – catalogued as “petty tyrants” – are but buffoons destined as their victims to be finally devoured; only a man following a path of power has a slight chance to escape to the common fate of the living beings. This relentless worldview is not so far of several esoteric streams, as in some ancient Greek mysteries where sole the initiate will know a valuable post mortem destiny, independently of morals, social status or intellectual abilities. We found also in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad this provocative statement: “There was nothing whatsoever here in the beginning. It was covered only by Death [mṛtyú], or Hunger, for hunger is death. He created the mind, thinking, ʽMay I be animated!ʼ[10] So Death created life for food, which is not a comforting view but pretty motivating to follow a spiritual path and is quite similar to the view of the Eagle perceived as the source of everything by the old Mexican seers, according to Castaneda. Besides immediate material benefits, the Vedic sacrifice was also intended to procure the real immortality, not that gross one researched by transhumanism and science. Castaneda gives in The Eagle’s Gift an incantation both in Spanish and English he received “for times when my task would be greater than my strength”, destined to reveal to him “a practical maneuver of the second attention”:

“I am already given to the power that rules my fate.

And I cling to nothing,

so I will have nothing to defend.

I have no thoughts,

so I will see.

I fear nothing,

so I will remember myself.

Detached and at ease,

I will dart past the Eagle to be free.”

In Castaneda’s work, there are a lot of doctrinal elements about perception, the couple nagual/tonal etc. and teachings which could be very useful to a differentiated man, such as dreaming – not the Freudian ordinary type of dreams of modern men, garbage can of repressed desires, but lucid or powerful ones –, stalking, not-doing, stopping the world, the possible use of entheogens, a non-ordinary way of walking, recapitulation, the grandness of death as adviser, and so on. We will only consider here the notions of warrior, impeccability, erasing personal history, and eliminating self-importance. First of all, life is an energy dispersion, both vital and subtle, ending finally in death, and that is the common lot of men from time immemorial. To gain power and thus to be able to get around the Eagle’s beak, to achieve the “totality of himself” or spiritual liberation asks to stop to behave as if we are immortal beings and refrain from energy wasting.

Amongst the means suggested by Castaneda and his mentors for a spiritual warrior to replenish his personal power, impeccability is of prime importance and accessible to everyone. Don Juan in Tales of Power defines it simply with these words: “Impeccability is to do your best in whatever you’re engaged in.” He answers later to an objection from Castaneda: “It’s not as complicated as you make it appear. The key to all these matters of impeccability is the sense of having or not having time. As a rule of thumb, when you feel and act like an immortal being that has all the time in the world you are not impeccable; at those times you should turn, look around, and then you will realize that your feeling of having time is an idiocy. There are no survivors on this earth!” Impeccability should not be confused with morality: it is the best use of our energy level while “most people move from act to act without any struggle or thought. A hunter, on the contrary, assesses every act; and since he has an intimate knowledge of his death, he proceeds judiciously, as if every act were his last battle.” (Journey to Ixtlan).

This echoes an analogous perspective in Ride the Tiger, when Evola writes about “acting without desire”, meaning: “without regard to the fruits, without being affected by the chances of success or failure, victory or defeat, winning or losing, any more than by pleasure or pain, or by the approval or disapproval of others. […] The higher dimension, which is presumed to be present in oneself, manifests through the capacity to act not with less, but with more application than a normal type of man could bring to the ordinary forms of conditioned action. One can also speak here of ʽdoing what needs to be doneʼ, impersonally.”

Referring to a statement by the French writer Charles Péguy, Evola remarks: “a work well done is a reward in itself, and that the true artisan puts the same care into a work to be seen, and into one that remains unseen.” In a society dominated by the utilitarian demands of yield and increased productivity, confusing action with agitation, unable to focus at length on one thing, it can be hard to practise it, but this is evidently a necessary attitude for a differentiated man.

In the modern era, normally a human being receives from birth a restrictive description of the world based on reason[11] that he will generally hold as the only true one, and which will be reinforced by the social institutions, forgetting that “it is monstrous to think that the world is understandable or that we ourselves are understandable” (The Eagle’s Gift). Consequently, the first challenge for a person engaged in a spiritual quest is to be able to adopt a non-materialistic description of the world and follow the precepts required to verify the validity of the way, in accordance with his own capacity, knowing that on the ultimate level, there exists no way and no description able to render in words the unknown and the unknowable. There are some similarities between the path of the warrior related in Castaneda’s writings and that of the Tantric vīra (hero), requiring a purification of the will and the release of bondage, keeping in mind that according to a Tantra cited in The Yoga of Power, “all the means employed must be experienced without disgust, concupiscence, or attachment”.

The excessive maintenance of our ego and self-importance – our “greatest enemy” – consumes a great amount of energy unnecessarily, which could be used for a higher purpose, and produces a terrible mental tension, often unconscious. The feeling that we are the most prominent being on earth renders us incapable to fully perceive the world around us, including its subtle levels. Hence the value of erasing personal history and of losing self-importance. Don Juan recalls in Journey to Ixtlan: “It is best to erase all personal history […] because that would make us free from the encumbering thoughts of other people.” Routines, contrary to the practices required by the way, make us vulnerable and transform us into preys. There are strategic means given in Castaneda’s work for eradicating self-importance and personal history such as control, discipline, forbearance, timing, will, to establish an inventory of habitual behaviours, and recapitulation[12], which sets free energy confined within us because of the impact of events experienced during our life. In The Fire from Within, don Juan explains: “Warriors prepare themselves to be aware, and full awareness comes to them only when there is no more self-importance left in them. Only when they are nothing do they become everything.”

This quotation is in accordance with the Traditionalist School: thus the epitaph hic jacet nemo “here lies no one” desired by Coomaraswamy or Evola’s consideration about the “active impersonality” of the absolute person, opposed to the passive impersonality suffered by the modern man, in a world marked by the anonymity of metropolises and the triumph of individualism combined with the rise of masses, since both are mutually reliant. In Ride the Tiger, Evola distinguishes between the person and the individual: the individual is a formless, numerical “theoretical unity”, while the person, as per its Latin etymology persōna is a “mask, character”, the mask that ancient actors wore in incarnating a given personage, having thus a typical, non-individual function. Contrary to the individual, the person “is not closed to the above”, but according to Evola’s words is “that which the man presents concretely and sensibly in the world, in the position he occupies, but always signifying a form of expression and manifestation of a higher principle in which the true center of being is to be recognized, and on which falls, or should fall, the accent of the Self.”

In the atomized world today in which we live, the use of Castanedian controlled folly and the art of stalking opposed to the ordinary madness of the human society could already be a concrete means of survival…

We will conclude our notes about “Death is a Spiral” with this sentence of don Juan from The Power of Silence: “man needs now, more so than ever, to be taught new ideas that have to do exclusively with his inner world – sorcerers’ ideas, not social ideas, ideas pertaining to man facing the unknown, facing his personal death.”

5. Credits

Credits for the music video, all material reworked:

- Tzompantli at Templo Mayor, Mexico City, photo by Scorh, 2007

- The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy, Mexican film directed by Rafael Portillo, 1958

- Tecpatl glyph and god Mictlāntēcutli from the Codex Borgia by Katepanomegas, 2009, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

- Spiral CIMG0420 by Daniel, 2011, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0

- Disc of Mictlāntēcutli, shown at the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, photo by Anagoria, 2013, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

- Picture of Mictēcacihuātl from the Codex Borgia

- Santa Muerte, Nuevo Laredo, photo by El Comandante, 2007, CC

Music video by Mordor, 2019; music by Mordor/Chopin, 2007. Some samples used in “Death is a Spiral” can not be properly credited due to the lacking references.

Recorded, mixed and mastered at Dark Sound Studio, 2007.

“Death is a Spiral” is dedicated to Carlos Castaneda.

[1] Luigi Russolo, quoted in Luciano Chessa, Luigi Russolo, Futurist: Noise, Visual Arts, and the Occult.

[2] Poem translated in English in Luciano Chessa, Luigi Russolo, Futurist: Noise, Visual Arts, and the Occult. The howler is one of the noise instruments invented by Russolo, producing a noise between that of a traditional string instrument and of that a siren.

[3] We use by convention the term “Aztec” (derived from the Nahuatl words aztecatl, singular, and aztecah, plural) instead of “Mexica” or “Mexitin” to denote the Nahuatl-speaking indigenous people that settled in the Valley of Mexico after an arduous migratory process, who employed themselves the endonyms Mēxihcah or Mexitin, and their allies, to avoid confusion with present-day people of the United Mexican States. “Aztec” is based on the notion that this group of tribes according to some ancient chronicles came from Aztlān, a mythical place of origin and ancestral home, often depicted as an island located vaguely in the north, which is symbolically in our view far more significant than the actual geographical locus, north being a place of origin in several traditions. In one account, when Huītzilōpōchtli, the tutelary deity of the Aztecs, ordered them to migrate, he also requested on the road that they change their ethnonym Azteca to Mexitin [Mexica].

[4] Extract from a poem quoted in Manuel Aguilar-Moreno, Handbook to Life in the Aztec World.

[5] Thus academic Wolfgang Haberland in his article La Vallée de Mexico published in Les Aztèques, Trésors du Mexique Ancien, considers that we should probably cut two zeros to the number of sacrificial victims during the enthronement of tlahtoāni (ruler) Āhuitzotl.

[6] In Nahuatl, there is the locution mictlāmpa “toward the region of the dead, the north”. For the place Hel ruled by the deity of the same name, there is succinct information in Snorri Sturluson’s Gylfaginning that “downwards and northwards (niðr ok norðr) lies the road to Hel”. In the Eddic poem Baldrs draumar, Óðinn reið niðr þaðan niflheljar til “rode thence down to Niflhel” to question a dead seeress. Niflhel “Misty Hel” might be identical to Hel or the lowest level of this realm. It is also Snorri who mentions that “those who die of sickness or old age” go to Hel.

[7] From Testimonies of Santa Muerte devotees from Tepito, quoted in Małgorzata Oleszkiewicz-Peralba, Fierce Feminine Divinities of Eurasia and Latin America.

[8] Published in Metaphysics, a collection of Coomaraswamy’s essays, edited by Roger Lipsey. The traditional psychology is of course not the modern psychology, as it is a pneumatology rooted in metaphysics and in the immortal Self rather than in the psyche.

[9] All excerpts from the Tantric texts quoted here are taken from Julius Evola, The Yoga of Power.

[10] English translation from The Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad with the commentary of Śaṅkarācārya by Swāmī Mādhānanda, revised in the light of the French one found in Jean Varenne, Cosmogonies Védiques. There are many discrepancies between the different available translations, due to the difficulty to render Sanskrit texts in modern languages, that often a Sanskrit word has multiple meanings and therefore the translator has to make a choice depending on the context, his own paradigms and understanding. The commentary of Śaṅkarācārya refutes the nihilistic viewpoint possibly suggested by “there was nothing…”, meaning in fact “there was nothing whatsoever differentiated by name and form here, in the universe, in the beginning, i.e. before the manifestation of the mind etc.”

[11] Reason is an useful tool that has unfortunately become an end in itself, a guard who turned into a jailer, focusing on an “obsessive manipulation of the known”. Beyond the duality of rational and irrational, there is the domain of the suprarational.

[12] Recapitulation is not a therapy based on speech like psychoanalysis. It consists of “recollecting one’s life down to the most insignificant detail” to lose the human form, defined as “a sticky force that makes us the people we are”, composed of habits and received opinions proper to the human affairs and conditioning us. In order to really change, a warrior must drop the human form. Recapitulation is also a key to shift the assemblage point located in our subtle body, by which we assemble the ordinary world or others. An involuntary shift of this point can cause great damages. Castaneda describes a recapitulation method using breathing, a crate, quietness and solitude in his writings, but there are other ones working on the “energy memory” of the major issues of our life. Since awareness is the Eagle’s food, he can be satisfied with a perfect recapitulation instead of consciousness. For Hinduism, the weight of the imprints and patterns which limits our freedom even goes back to well beyond the events experienced in one incarnation.