Part I available here.

4. Of the Aztec cosmic cycles and the mythos of the five Suns

“The Toltecs have been taken, alas, the book of their souls has come

to an end, alas, everything of the Toltecs has reached its conclusion, no

longer do I care to live here.”

– Extract from a song of the antique Quetzalcōātl

cyclus in Ancient Nahuatl Poetry, translated by Daniel G. Brinton.

The Aztecs had not only a sense of history and chronicled the important events of their past, but tried to measure and manipulate time with complex and accurate calendric systems, and decrypt the repeated patterns of events. As most of the traditional cultures, they had too a cyclical conception of time – or more accurately, spiralic, for it is not exactly an eternal recurrence with the repeat of exactly identical events over and over again – different of the strict linear view peculiar to modernity, constructed on the idea of continuous progress, secularized legacy of some religions like Abrahamic monotheisms, at least in their exoteric beliefs. The two perspectives can even partly co-exist in our society today, with the annual calendar of the feasts still in existence celebrating observances like Christmas or the New Year, although they are often for most people henceforth empty of a profound meaning if we compare them to the festivities of traditional societies. The Aztecs also had their own conception of the cosmic cycles or ages presented in a temporal succession including multiple creations and destructions, a doctrine that exists in several traditions such as Hinduism. According to René Guénon in Traditional Forms and Cosmic Cycles, “In the most general sense of the term, a cycle must be considered as representing the process of development of some state of manifestation, or, in the case of minor cycles, of one of the more and less restricted and specialized modalities of that state.”

It is mainly in Purānic Hinduism that the doctrine of the cosmic cycles was certainly the most highly formulated: the development and the dissolution of an universe – or multiverse – and species is governed by great cycles of an astounding duration subdivided into smaller ones. To name a few, we have kalpa-s, manvantara-s, mahāyuga-s, every mahāyuga being divided itself into four yuga-s including the (in)famous Kali-Yuga (literally meaning “age of the losing side of a dice” or “age of Kali”, a demon not be confused with the goddess Kālī), which is our cursed present era, although there were previously other Kali-Yugas. Every yuga produces a gradual spiritual decline as decrepitude increases in prominence – albeit temporary redressements are still possible –, and this doctrine is one of the key elements of our worldview: to identify the deep reason of an issue is the first step to find a solution to remedy it. Hinduism for instance has envisaged various appropriate means to respond to this critical situation and cyclical determinism in view of achieving spiritual liberation, and Left-Hand Tantrism undoubtedly is one of them.[22] Even in the worst age, there are still some – rare – possibilities to seize.

Eliade in his novel Dayan speaks a little of the Aztec view of the cosmic cycles, without going into detail, for it is not an academic essay but a work of fiction, which does not mean that it is less important for us, quite the contrary. He simply mentions a “heavenly time” ending with Cortés’ disembarkation on the Mexican coast, and consequently starting a “hellish time”; he attributes a duration of 13 × 52 years to the heavenly period, that is 676 years, and 9 × 52 years to the hellish period, that is 468 years. We have respected in “Urzeit” the indications of Eliade, although we have partially completed them with some of the surviving data supplied by available indigenous and Spanish sources. For the Aztecs, before our current Sun, four Suns have previously existed since the initial creation of the world, each of which ending with a disaster, making thus a total of five Suns or ages. Each Sun is named after the power that rules over it or the Element that destroyed – or for our era, will destroy – the world and mankind in question and the occurrence day sign used in two of the indigenous calendars, the ritual and divinatory 260-day tōnalpōhualli and the annual 365-day (360 + 5 nameless and “useless” days) xiuhpōhualli.

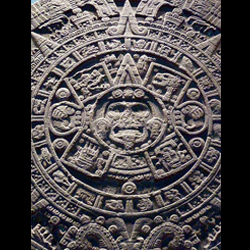

There are various, contradictory versions of the mythos of the five Suns – we preferably use interchangeably the terms “myth/mythos” instead of that of “legend”, which is often the degraded transposition of a myth –, with a discrepancy of dates, duration, order and number of the eras in the sequence, and so forth; therefore it is hard to reconstruct a hypothetical canonical model, that might have never existed, for variations on a myth are usual in traditional societies, without speaking of the defectiveness of the transmission of native ancient lore due to the Conquest. Variations can be the opportunity to highlight other perspectives too, for a myth can be told from different viewpoints with equal authority. If the conception of four successive Suns was likely Mesoamerican, the addition of a fifth Sun seems to be specifically Aztec and was in phase with their horizontal spatial division into quadrants, each age being in relation with a cardinal direction and an element, whereas the centre is the axis mundi or navel of the world associated with their fire god, an idea metaphorically akin to the Vedic one illustrated by the following quotation from Taittirīya Saṃhitā: “Kindled on earth’s navel, Agni [the fire god] we invoke”. The day signs of the end of the Suns are graphically represented among other things on the remarkable monumental sculpture Piedra del Sol, the famed Sun or Calendar Stone, whose the carved motifs covering its surface refer to important components of the Aztec worldview; thus it is not just a fine and elaborated piece of art released for aesthetic purposes, resulting from a random inspiration, but above all a means to express mythical, religious and cultural elements from their Weltanschauung. Furthermore, when we were in front of the sculpture exhibited at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, we perceived a strong “energy” (Skt. śakti) originating from it, thus undoubtedly confirming that we were not dealing with profane ornamental art.

Drawing to one version of the myth of the five Suns dating from 1558, contained in the Leyenda de los Soles and translated from Nahuatl by Miguel Léon-Portilla[23], we indicate the order of the Suns, the day of their end, their duration and some details:

- First Sun: nāhui ōcēlōtl (4-Ocelot or 4-Jaguar), that lasted 676 (13 × 52) years. People were finally jaguar-eaten, a chthonic animal. Element: Earth (Note: Elements are primarily “cosmic forces” and “subtle roots” of the gross material elements or states of matter).

- Second Sun: nāhui ehēcatl (4-Wind), that lasted 364 (7 × 52) years. People and the sun were carried away by the wind and men turned into monkeys. Element: Air.

- Third Sun: nāhui quiyahuitl (4-Rain), that lasted 312 (6 × 52) years. People were fire-rained and turned into turkeys, the sun was burnt by fire. Element: Fire.

- Fourth Sun: nāhui ātl (4-Water), that lasted 676 (13 × 52) years including a 52-year flood. People were swallowed by water, heavens collapsed upon them and they turned into fishes. Element: Water.

- Fifth Sun (“this is our Sun, the one in which now we live”): nāhui olīn (4-Movement or 4-Earthquake). The text indicates that “it was also the Sun of Our Lord Quetzalcōātl in Tula” and a “divine hearth” in the city of Teōtīhuacān, “the place where one becomes a god/spirit”. People will perish due to earthquakes and hunger. Element: maybe Earth or none, or a synthesis of the four.

The duration of each age is a multiple of the Aztec “century” of 52 years. Note that the 676 (13 × 52) years of the first and fourth Suns corresponds to that of the “heavenly period” given in Dayan by Eliade. The number 13 could symbolize the thirteen superposed layers of the celestial plane mentioned in some sources, and by assigning to the “hellish period” a duration of 9 × 52 years, Eliade had perhaps in view the nine levels of the Aztec Underworld. We also notice that when adding the duration of the second and third Suns, that is 364 and 312 years, there is a total of 676 years equal to the respective duration of the first and fourth Suns, and that the sum of the multipliers 7 and 6 gives 13. The importance of the fifty-two year count for the Aztecs was directly related to the two main types of calendars in use, the 260-day tōnalpōhualli made up of 20 groups of 13 days and the 365-day xiuhpōhualli, made up of 18 “months” of 20 days, to which were added five days regarded as unlucky at the end of the year, the nēmontēmi.

Because of their different way to compute time, a concordance of the beginning day of the two interrelated calendric systems would occur once every fifty-two years of 365 days. It was regarded as a liminal time of terrifying uncertainty by the Aztecs, for they thought that the sun could never rise again and it was marked by the celebration of a crucial feast called toxiuh molpilia “our years were bound” including the New Fire Ceremony in a specific locus to ensure the rebirth of the sun and the start of a new cycle. All fires were extinguished, a new one using perhaps 52 pieces of wood or a bundle of 52 sticks symbolizing the old 52 years was ignited by drilling during a sacrifice and its flame distributed to temples, cities and domestic hearths, a conception perhaps similar to that of some Indo-European traditions. To give a single illustration, according to The History of Ireland by Geoffrey Keating: “it was there the Fire of Tlachtgha was instituted, at which it was their custom to assemble and bring together the druids of Ireland on the eve of Samhain to offer sacrifice to all the gods. It was at that fire they used to burn their victims; and it was of obligation under penalty of fine to quench the fires of Ireland on that night, and the men of Ireland were forbidden to kindle fires except from that fire”.[24] In The Myth of the Eternal Return, Eliade explains thus the aim of this “termination ritual”: “The ritual extinguishing of fires is to be attributed to the same tendency to put an end to existing forms (worn away by the fact of their own existence) in order to make room for the birth of a new form, issuing from a new Creation.”

Another version of the mythos of the five Suns can be found in the Historia de los Mexicanos por sus Pinturas. It adds extra data to those given previously such as the type of food eaten by people in every age, and the fact that the men of the first era were giants, but it shows some divergences: the duration of the Suns for example is 676-676-364-312 years. It also provides significant information missing in the Legend of the Suns on the gods involved in the process. If we extract some relevant elements of the story for our purpose[25], it appears that there was originally one god named Tōnacātēuctli who took for wife Tōnacācihuātl, who created themselves and were perpetual inhabitants of the thirteen heaven, the metaphysical region. They engendered four sons, rulers of the cardinal points, the four Tezcatlipōca-s, including the Black Tezcatlipōca and the White one, Quetzalcōātl, who are engaged in a constant warfare with each other. After the shaping of the cosmos by the four gods and the creation of other deities, to complete or replace the half-sun at that time giving very little light, the Black Tezcatlipōca made himself a sun and it was the first age populated by giants. It finished when Quetzalcohuātl gave his brother a blow with a great stick, and threw him over into the water, where he turned into a jaguar, slaying the giants. Therefore Quetzalcōātl became the second Sun and a new mankind emerged but the god was eventually thrown out by Tezcatlipōca, and a terrible wind arose which carried away all the men, except a few who turned into apes and monkeys. The next Sun was Tlāloc, the rain god; when his time was over, Quetzalcohuātl sent down a rain of fire from heaven, destroying the third humanity and made Tlāloc’s wife and sister, the sweet waters goddess Chālchihuitlīcue, the fourth Sun. She was deprived of her function by a deluge so great that heavens themselves felt, and the waters swept away all the men that were, and from them were made all sort of fishes. After the deluge, heavens were lifted and a new mankind was made as well as a new Sun, which should eat hearts and drink blood, so to feed it, continual warfare is mandatory.

The account also refers to the new sun as Quetzalcōātl’s son, “heated red hot in a fire”, and to the moon as Tlāloc’s son, who was thrown by his father “in the cinders from whence he issued forth as the moon, for which reason he appears ashy coloured and obscure.” It partially echoes the myth of the sacrifice of Nanāhuātzin, a modest and diseased god, and Tēcciztēcatl, an arrogant one, during a gathering of the gods in the pristine city of Teōtīhuacān. Tēcciztēcatl volunteered to be the fifth Sun but was afraid to jump into the bonfire, and so the first god to sacrifice himself was Nanāhuātzin, who became the new sun and took the name of Tōnatiuh. Only then Tēcciztēcatl leapt into the fire and became the moon. Other gods began to immolate themselves for the purpose of starting the first solar cycle, and subsequently human beings have to be sacrificed to ensure the movement and the strength of Tōnatiuh. It is one of the explanations why offerings, autosacrifice, vegetal, animal and human sacrifice were essential for the Aztecs in order to provide the energy necessary to feed the gods: in their view sacrifice was not a sadistic act of gratuitously cruelty but a fair exchange based on the principle of reciprocity and a kind of debt-payment to assure the survival of the world; without it, everything will cease to exist. “We mortals owe our life to sacrifice”, says the Leyenda de los Soles, “because for us did the gods sacrifice”. If the gods are real incorporeal beings sometimes benevolent and providers of gifts (the first being life), they may also be frightful, arbitrary and malevolent: they are amoral, not bounded by human values and morals. Just as for spirits, it may be necessary to propitiate them by sacrifice, especially in times of trouble. And it should be not forgotten that for various academics the number of the sacrificed victims was greatly exaggerated by the Spanish chroniclers as a strategy to justify the crimes of their own compatriots against the Mesoamerican people[26], a narrative still in use today in other contexts.

There are other Aztec myths of particular interest, such as the creation of the current mankind of the fifth Sun from the bones of previous men by Quetzalcōātl, after a journey to Mictlān, the Underworld, and some tricks done by Mictlāntēcutli, the Lord of the place of the dead, to stop him, but we will not discuss them here. From the Hindu perspective, the five cosmic ages of the Aztecs like those of the Graeco-Roman tradition or the four periods of metal mentioned in the Mazdean compendium Dēnkard will partly correspond to the four yugas contained in one mahāyuga, itself part of greater cycles. A difference should be noted: the Aztec view apparently does not include the notion of a worsening of the spiritual situation with each age. On the contrary some scholars insist on the idea of a progress occurring with each Sun, using as argument among others the fact that maize, the Mesoamerican staple food, was available only from the fifth Sun; men’s food getting successively closer to that ideal. It seems also that for the Aztecs our era was the best of the Suns for it is situated at the centre, the foundational point. We may however point out that our current Sun is the only one that requests sacrifice because of its weakness and that historically the Aztecs regarded the era of previous cultures (like those from Tula, Teōtīhuacān and perhaps the Olmecs, “mother culture” of Mesoamerica) as a kind of golden age they attempted to recreate. If we accept the thought of a progress, it is certainly neither an evolutionary process (some species such monkeys are the remains of previous human races) nor a continuous progress, as each age is brutally interrupted; it would be more like several empirical tests conducted by the gods to finally find the right formula for a type of men suitable for them, although the mankind of the fifth Sun is still doomed to disappear too.

We prefer to stay in line with the Aztec agonistic worldview, that could be likely partially understood by ancient Norse peoples: the cosmos is not static but dynamic, the changing, violent place of a constant struggle between opposing and complementary divine powers generated at the beginning by a dual principle which is sole whole, where destruction inevitably follows creation in a cyclical manner. The potentialities of each main cardinal point, Element and of their rulers are successively actualized. We live in the instability of a continually threatened world where nothing lasts forever, where the most beautiful flowers fade away too, as a song of the great king-poet and philosopher Nezahualcoyōtzin reminds us: “All things of earth have an end, and in the midst of the most joyous lives, the breath falters, they fall, they sink into the ground. All the earth is a grave, and nought escapes it; nothing is so perfect that it does not fall and disappear.”[27] Furthermore, time for the Aztecs was not composed of an uniform series of qualitatively identical instants. In La Pensée Cosmologique des Anciens Mexicains, anthropologist Jacques Soustelle supplies an interpretation of their view on space and time:

“Mexican cosmological thought does not make a sharp distinction between space and time. It refuses, above all, to think of space as a neutral and homogenous medium independent of unfolding time. Time unfolds in the form of heterogeneous events whose peculiar characteristics follow one another with a predetermined rhythm and cyclical manner. […] The world can be compared to a great stage upon which different multi-coloured lights, controlled by a tireless mechanism, project reflections that follow one after the other, maintaining for a limitless period an unalterable sequence. In such a world, change is not conceived as the result of a gradual evolving or ‘becoming’ in time, but rather as a brusque and complete mutation: today it is the East that rules, tomorrow it will be the North; today we still live under a favourable sign and we shall, without any gradual transition, pass into the fatal days of the nēmontēmi. The law of the universe is the succession of different and radically separated qualities which alternately prevail, disappear and reappear without end.”[28]

5. Of time, its abolition and immortality

“The metaphysical doctrine simply contrasts time as a continuum with the eternity that is not in time and so cannot properly be called everlasting, but coincides with the real present or now of which temporal experience is impossible.” – Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Time and Eternity.

We should like to conclude our notes by touching shortly on the chief subject addressed by the novel Dayan and our song “Urzeit”, namely the issue of time, which is a jail, and its temporary or definitive abolition, a goal pursued by Constantin Orobote, the main protagonist of Eliade’s short story. It is not our intention to discuss here the possibility of using mathematics to overcome time and consequently death; in his search of the “ultimate equation”, Orobote, a mathematical genius working mainly on a theorem proposed by the logician, mathematician, and analytical philosopher Kurt Gödel, finally figured out through a weird experience (thanks to his old guide, a sort of World-soul, anima mundi) that time can expand and contract depending on the circumstances and that it can be compressed in two senses: forwards, towards the future, and backwards, towards the past. On the contrary, we personally favour elements of the perennial wisdom mentioned in Dayan such as myths, legends, poetry and so on, that far from being obscurantism, superstition, and false beliefs are in our view a precious means to decipher the mysteries of the world beyond scrutiny of its gross components and the level of immediate ordinary experience, provided that the mentality of the seeker is adequate to the material studied and, as myth and ritual are often closely interrelated, put into practise when possible. Rationalistic knowledge is not in itself sufficient to achieve the gnostic goal of liberation and inner transformation that we set ourselves following traditional models and our own experiences. In the words of Seyyed Hossein Nasr, “One must also ‘become’ what one knows”.

A lot of traditions have considered that time can be overcome and its noxious effects reversed one way or another, even if this quest is not always successful, as evidenced by the famous Epic of Gilgameš: the hero, “king without equal”, went on a long, hard journey in search of immortality to eventually receive a plant against decay and with rejuvenating powers named “The Old Man Becomes a Young Man”, performing superhuman feats to this end. Gilgameš after having acquired the plant bestowing a “life-without-end” was however unable to consume it because of the intervention of a snake that stole it while he was bathing. At least the hero got the relative immortality of the “imperishable, unfailing fame” by his deeds recorded by the means of epic poetry; his renown well survived after his death. The episode of the subterranean tunnel guarded by two scorpion monsters, where “dense was the darkness, light there was none”, that Gilgameš has to cross before seeing the garden of the gods is actually mentioned in Dayan. The search of an everlasting life that we call “corporeal (or physical) immortality” is an old dream that maybe some yogis, Taoists and alchemists have partly obtained, in order to gain more time to achieve their spiritual quest. Today scientists and advocates of transhumanism are working to obtain the same result, but for a mundane goal and with different means, considering and turning the physical body into a machine or a biochemical algorithm, logical consequence of their materialistic perspective: if we are exclusively corporeal beings and nothing exists outside “matter-energy”, then the sole possibility of solving the problem of death (or at least to repel it further) is by cloning or to create an “upgraded man” by technology, and/or intervening in the programming that sentences us to death.

It is however not corporeal immortality that we have in mind when speaking about the abolition of time and real immortality, for “No one becomes immortal with the body” (Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa). In his essay Ātmayajña: Self-Sacrifice, Coomaraswamy acknowledges in the Vedic sacrifice (yajñá) performed by priests for a sacrificer “for the winning of both worlds” (the terrestrial and the Otherworld) two types of immortality that can be achieved. One is the “relative immortality” of not dying prematurely, living the full term of one’s life on earth with an increase of possessions and progeny founded on the principle of reciprocity do ut des “I give that you may give” between men and deities, knowing that like for the Aztecs “Actually, sacrifice is the food of the gods” (Ś. B.) and the payment of a debt owed to the gods, including Death, due to human birth. The other immortality is the “absolute immortality”, i.e. the deification of the sacrificer, which requires however the comprehension of the ritual as a series of symbolic acts, which can be used as supports for contemplation, and of the substantial identity between him and the victim: what is sacrificed is the mortal, psychophysical self – a compound, “host of elemental beings” – to ensure the new birth of the initiate. Thus “The sacrificer’s ‘death’ is at the same time his salvation; for the [immortal] Self is his reward.”[29] The climbing rite of the sacrificial post (yūpa) described in some Brāhmaṇa-s involves too initiation and symbolic death, and was considered not without risk: either the sacrificer is no longer a common man but becomes a deva “god”, or if he does not return again to the terrestrial world, he may go to the suprahuman one, or go mad or perish consumed by the sacrificial fire. Besides, the Vedic sacrifice is the reactualisation or mimesis of the archetypal First Sacrifice providing the elements of the world, which was done by the First Sacrificers in illo tempore, “in that time”, the primordial, mythical time not to be found in the historical past or present: “We [the sacrificers here and now] must do what was done by the gods [the original sacrificers] in the beginning”.[30] For the cosmos and living beings are subject to the law of becoming and decaying, and need a periodical renewing and strengthening by repeating what occurred originally; hence the importance of the New Year festival for instance in several traditions or the Aztec New Fire Ceremony toxiuh molpilia.

The mention of the primordial time leads us to the distinction of “profane duration”, the quantitative ordinary, irreversible time measured by clocks, and “sacred time”, a reversible “succession of eternities”, made by Eliade in The Sacred and the Profane: “religious man lives in two kinds of time, of which the more important, sacred time, appears under the paradoxical aspect of a circular time, reversible and recoverable, a sort of eternal mythical present that is periodically reintegrated by means of rites. This attitude in regard to time suffices to distinguish religious from nonreligious man; the former refuses to live solely in what, in modern terms, is called the historical present; he attempts to regain a sacred time that, from one point of view, can be homologized to eternity.” While for nonreligious man, although aware too of times of different intensities and rhythms – one minute of torture is not the same that one minute of pleasure –, time can show neither break nor mystery; it is just the routine of a “day after another day”, a purely human experience, with no sudden possible irruption of the numinous, whether it is its bright or dark, terrible face. In the festivals of the liturgical time of the calendars, besides their immediate utilitarian purposes, according to Eliade “the participants recover the sacred dimension of existence, by learning again how the gods or the mythical ancestors created man and taught him the various kinds of social behavior and of practical work”; they experience “the same time that was created and sanctified by the gods at the period of their gesta [deeds], of which the festival is precisely a reactualization […] For the sacred time in which the festival runs its course did not exist before the divine gesta that the festival commemorates. By creating the various realities that today constitute the world, the gods also founded sacred time, for the time contemporary with a creation was necessarily sanctified by the presence and activity of the gods.”[31] Hence religious festivals are a way to communicate with the divine world, an attempt to restore the balance of the cosmos and to be periodically in the presence of the gods.

Our own experience shows that if we can hardly influence the macrocosmic or physiological time (except with some yogic practices in the second case), we can however intervene on the subjective time. When a ritual is adequately performed in an ideal spatio-temporal centre with the real presence of gods or other incorporeal beings, the perception of time and space differs significantly of the ordinary one, with this particular feeling of a “time outside of time”, an instant without duration. It is not a concept created by the mind but really a perception of the different quality of the “sacred space-time” established for and by the event. This quality can even expand far beyond the physical limits of the consecrated place, as a ritual also produces an “energy” (śakti). It is worth noting that it may lead the sensitive participants to an altered state of consciousness without resorting to power-plants (entheogens) for instance. We could say it is a temporary abolition of the profane duration and a regeneration of time due among other things to the fact that “Through the paradox of rite, every consecrated space coincides with the center of the world, just as the time of any ritual coincides with the mythical time of the ‘beginning’.”[32] The degree of the presence of incorporeal beings and their positive or negative involvement as well as the proper performance of the ritual are evidently determinant.

The festivals that made up the ritual calendar are a means to put men in phase with the cycles of nature and cosmos too; however, there were people not completely satisfied with the closed circle of the year, for it also reveals the precarious situation of the cosmos periodically created and destroyed, and men according to the Aztec myth of the five Suns are threatened with extermination. Therefore some individuals were in quest not for a temporary but definitive abolition of time and space, a release of the spatio-temporal slavery. India is specially interesting in this respect, with the notion of an Absolute beyond contraries and polarities, and the possibility to achieve mokṣa, the spiritual liberation. If we quote again Eliade:

“for the yogins and other contemplatives the summum bonum [the highest good] transcends the cosmos and life, for it represents a new existential dimension, that of the unconditioned, of absolute freedom and beatitude, a mode of existence known neither in the cosmos nor among the gods, for it is a human creation and accessible exclusively to men. Even the gods, if they desire to obtain absolute freedom, are obliged to incarnate themselves and to conquer this deliverance by the means discovered and elaborated by men.”[33]

His remark about the gods requires some comment, because some spiritual traditions differentiate one or several greater deities superior to the common gods. In the schools of Tantrism and Śāktism practising a kind of henotheism, depending on the orientation of the adepts, the Great Goddess Mahādevī (whatever Her names: Śakti, Devī, Kālī, Durgā, Pārvatī…) or Śiva, or their divine couple inseparably united, the Two-in-One, is declared to be the supreme divinity, equivalent in fact to the Brahman, the Absolute: “Yogins, seers of the absolute truth call me, O Great King, as composed of Śiva and Śakti, the Supreme Brahman, the absolutely Supreme entity by the nature of my own Self”, says the goddess Pārvatī in the Devī Gītā. Thus in Śāktism, the Great Goddess can be seen in the same time as granter of enslavement and of liberation, the basis of the true reality and existence, substratum of the cosmos and the cosmos itself, both wholly transcendent and immanent; consequently She is the essence of the other gods and sentient beings too. The gods, of whom they are many classes and degrees, are certainly the highest inorganic beings in the cosmic hierarchy; nevertheless, it is said that themselves and demons still worship in secret the supreme Śakti, for they are plural manifestations of Her identified to the ultimate reality. In the Devī Gītā, She asserts that “the different deities are but the parts and parcels of my own energy”.[34] Besides, in Tantra or Āgama texts, Devī (the Goddess), Śiva, or Viṣṇu are often petitioned to reveal the metaphysical truths and adequate means to overcome the fundamental ignorance (avidyā or ajñāna, nescience), root-cause of the human bondage and of the cosmic flow: an epithet of Durgā signifies “liberatrix from the world of births and deaths”, and in a Purānic eulogy to the Devī, She is addressed in the following terms by the gods: “Thou art the germ of the universe, thou art Illusion [in the sense of “appearance”, māyā, the veil or power that obscures the Absolute] sublime! All this world has been bewitched, O goddess; Thou indeed when attained art the cause of final emancipation from existence on the earth!”[35] (i.e. liberation, mokṣa or mukti, the supreme worth of human life).

If now we turn to the Aztecs, Léon-Portilla in Aztec Thought and Culture refers to a doctrine developed by Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcōātl, king-priest of Tula, the capital of the Toltecs, including perhaps the possibility to overcome our transitory world and find the sole stable “region” beyond the primordial waters and a world constantly experiencing conflicts. This region is named Tlīllān Tlapallān, “Place of the black and red colour”[36], the location of Wisdom, a mythical toponym built on the same model that the difrasismo (idiomatic complex) in tlīlli in tlapalli “the black, the red [inks, used for the pictorial books]”, meaning “writing and wisdom”. According to Léon-Portilla and the Anales de Cuauhtitlan, Topiltzin Quetzalcōātl paid honour to the supreme dual principle Ōmeteōtl in the forms of the Lord and Lady of Our Sustenance and led a life of meditation and retreat, establishing as king a sort of golden age. But he has to leave Tula because of the activities of sorcerers or demons (the text names among others Tezcatlipōca) who wanted to sacrifice people while he was opposed to this practice, favouring autosacrifice (ritual extracting of one’s own blood) and animal sacrifice (snakes, birds and butterflies[37]) to satiate the needs of the gods. After a series of successful tricks and magical deceptions done by the demons, Topiltzin Quetzalcōātl finally departed from the city, broken, with his servants and went to Tlīllān Tlapallān in order to burn himself, then entered the sky and turned into the Morning Star (Venus), becoming the Lord of the Dawn, a form of the god Quetzalcōātl. So if the story is not one of the liberation and absolute freedom sought by Tantric adepts, it could nevertheless be an example of apotheosis, in the sense of the deification of a being able to quit the human condition and (re-)gain a higher divine state.

The Nahuas knew a type of man, the tlamatini, a word meaning “he who knows something”, generally translated as “wise man”, characterised notably by the fact that “he knows what is above us (topan), the world of the gods, and in the region of the dead (Mictlān)”. Besides obvious shamanic connotation, according to Léon-Portilla, “The idiomatic complex topan, mictlān carries the meaning, ‘what is beyond our knowledge, what is in itself beyond experience’. The Nahuatl mind formulated what we today would call a metaphysical order or noumenal world. Its counterpart is the world itself, cemānāhuac, ‘that which is entirely surrounded by water’. At other times, as has been noted, a contrast is made between what is ‘above us, the beyond’ and ‘what is on the surface of the earth [tlālticpac]’ […] On the one hand, there is that which is visible, immanent, manifold, phenomenal, which for the Nahuas was ‘that which is upon the earth’, tlālticpac; on the other, there is that which is permanent, metaphysical, transcendental, expressed in Nahuatl as topan, mictlān, ‘what is above us and below us, in the region of the dead’”.

The term tlamatini also refers to the nāhualli “magician, sorcerer, one who uses spells and incantations”, who had notably the ability to shapeshift into the animal form of his personal guardian spirit and other “supernatural” powers. The word written nagual or nahual will be later popularized by Carlos Casteneda and various authors as one term of the opposing and complementary pair tonal/nagual and as a title for “the leader or teacher of a group of apprentices in the art of mastering awareness”. The highest goal in the path described in Castaneda’s books is certainly to escape from the usual fate of living beings: their awareness enriched by experiences is doomed to be devoured by the Eagle, the supreme power, source of all sentient beings, that governs all destinies and whose emanations are made out of time, also called the dark sea of awareness. Two of the means used for that purpose are impeccability and the technique of recapitulation, allowing the practitioner to clean his memories of people, places and the feelings associated with them, in order among other things to lose the human form conditioning us. The human form is defined by Castaneda in The Wheel of Time as “a conglomerate of energy fields which exists in the universe, and which is related exclusively to human beings. Shamans call it the human form because those energy fields have been bent and contorted by a lifetime of habits and misuse.” Impeccability and giving our life experiences to the Eagle before death offer us a “chance to have a chance” to not end up in his beak, for he may be contented with a perfect recapitulation instead of awareness: “To die and be eaten by the Eagle is no challenge. On the other hand, to sneak around the Eagle and be free is the ultimate audacity” (The Eagle’s Gift). We can partly compare recapitulation with the burning of the vāsanā-s (past imprints, including not only individual memories of one’s present existence, but also the collective, and karmic residues of past lives) pursued by the yogi in order to free himself and “to abolish the work of time”. Eliade writes in The Myth of the Eternal Return about the Buddhist perspective: “The only possibility of escaping from time, of breaking the iron circle of existences, is to abolish the human condition and win nirvāṇa.”

In the end, the definitive abolition of time for a seeker of the ultimate reality is achievable only when he is freed from the conditioned human state as well as others even higher, once and for all, thus becoming according to Hinduism either a jīvan-mukta, one who is liberated in this life, being permanently in the paradoxical eternal present, the real eternity, or a videha–mukta, who obtains liberation solely when “out of his bodily form”, i.e. at the moment of his death. A comment from Ādi Śaṅkarācārya, one of the great masters of Advaita Vedānta, the non-dualistic school of Hinduism, may help to give an idea of the ultimate “natural state” achieved by a yogi delivered in this life:

“He who has made the pilgrimage of his own ‘Self’, a pilgrimage not concerned with situation, place, or time [or any particular circumstance or condition], which is everywhere [and always, in the immutability of the ‘eternal present’], in which neither heat nor cold are experienced [no more than any other sensible or even mental impression], which procures a lasting felicity and a final deliverance from all disturbance [or all modification]; such a one is actionless, he knoweth all things [in Brahma], and he attaineth Eternal Bliss.’”[38]

6. Credits

“Urzeit” is dedicated to Mircea Eliade, with a special thought for Cuāuhtemōctzin, the last Mexica tlahtoāni before the Spanish dominion.

Reworked material used for the music video:

- The Woman God Forgot (1917), by Cecil B. DeMille

- The Man Without Desire (1923), by Adrian Brunel

- ¡Que viva México! (1932), by Sergei M. Eisenstein

- Zoom into the Triangulum Galaxy by NASA, ESA, & G. Bacon (STScI)

- Aztec Calendar (Sunstone) reproduction (2012) by Karnhack, license CC BY 3.0

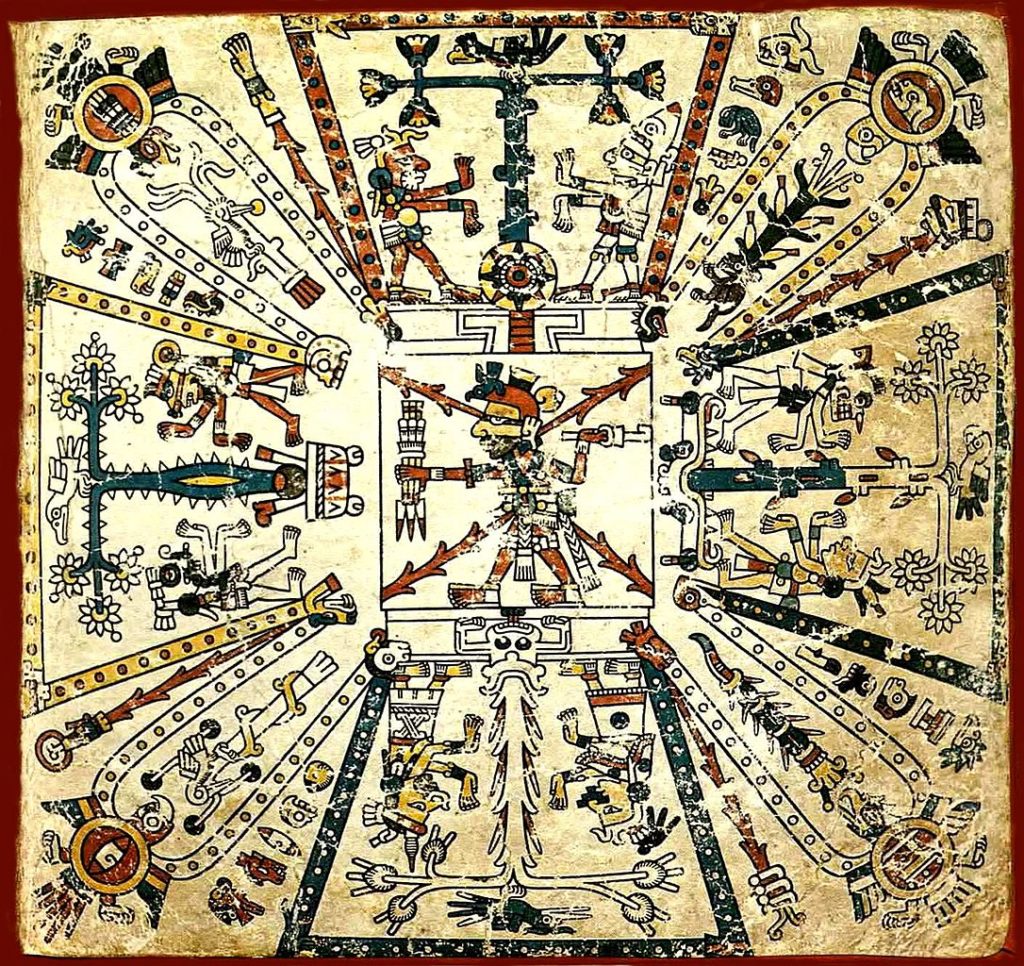

- God Tezcatlipōca (2009) from the Codex Borgia by Katepanomegas, license CC BY-SA 3.0

- Gods Quetzalcōātl & Tlāloc (2011) from the Codex Borgia by Eddo, license CC BY-SA 3.0

- Goddess Chālchihuitlīcue from the Codex Rios

- God Huītzilōpōchtli from the Codex Borbonicus

- Aztec solar disc & gold glyph (2018) by Adam Smith, license CC BY-SA 4.0

- Cuāuhtli, olīn, miquiztli & tecpatl glyphs (2012) from the Codex Borgia by Chaccard, license CC BY-SA 4.0

- Beatrice Addressing Dante (1824) by William Blake

- Goddess Cōātlīcue by Giggette

Music and words by Scorh, 1996-1997. Music video by Scorh/Vorknasor, 2019. All texts are under the license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Mordor were at the time of this live recording:

Scorh Anyroth – voice, guitar, machines, drones

Flore de la Mandragore – female voice

Dam Gomhory – bass, machines

S3th – percussion & guitar

Farkás – drums & percussion

H. G. – visuals

[22] See our short essay about the track “Der Ritt auf dem Tiger”, especially the section 3. Of Tantrism and the “differentiated man”, for some basic information about Tantrism and Evola’s “differentiated man”, a type of man capable to make effective use of the calamitous spiritual situation in the modern world, mentioned in his book Ride The Tiger and inspired by Left-Hand Tantrism, Nietzsche, and his own path. If the Kali-Yuga is etymologically not the Age of Kālī, due to its dark character it can be structurally associated in a play of words with the black-skinned goddess, the implacable mistress of Time.

[23] In Aztec Thought and Culture, op.cit. The author considers that this account “appears to be the most complete and most interesting, principally because of its antiquity.” For him, the form of writing indicates it was probably used as a commentary on a native manuscript.

[24] The Old Irish feast Samain was an annual feast of probably several days celebrating both the end of a year and the beginning of a new one. For more details, see our notes Les Armées de Sauron – 1997 Samain Live Act. The difference with the Aztec New Fire Ceremony is that Samain was every year a dangerous, liminal time. The Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún gives more information about the Aztec ceremony in his compilation Historia Universal de las Cosas de Nueva España, translated into French as Histoire Générale des Choses de la Nouvelle-Espagne. There was an annual Aztec festival performed during the last month of the year using a new fire held in honour of the fire god Xiuhtēuctli, and the inauguration of a newly built house required the lightning of a new flame inside too. The fire kindled by drilling in the New Fire Ceremony is perhaps a mimesis of the first one lit by the gods.

[25] We mainly rely on the English translation History of the Mexicans as Told by Their Paintings, by Henry Phillips Jr, 1883, edited later by Alec Christensen, available on the website of the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. We have replaced the original spelling of the names of the deities in the text by the usual Classical Nahuatl when possible – the same applies for other Nahuatl words in our essay –, knowing that the reconstructed forms may vary from one author to another; we have very briefly summarized the theogony, cosmogony and anthropogony, suppressing many events, for the goal is just to supply some information on the Suns and the gods concerned. Some remarks:

– The two other Tezcatlipōca-s, the Blue and the Red, are generally identified with Huītzilōpōchtli and Xīpe Totēc. The Black Tezcatlipōca (also written Tēzcatlepōca or Tezcatl-Ihpōca), a warrior teōtl often associated with the night sky and winds, north and sorcery, was compared to Lucifer according to the interpretatio christiana of Bernardino de Sahagún: “This evil Tezcatlipōca, we know, is Lucifer himself”.

– For the third Sun, the account speaks of a “Tlalocatecli, the god of the lower regions”, but it must be corrected as Tlāloc according to Léon-Portilla. Tlāloc is also a thunder-god, that which can explain the fire rain bringing to an end that era.

– The text cites the fierce earth monster Tlāltēuctli, also called Cipactli “crocodile, alligator”, the first day of the tōnalpōhualli, which is the earth floating in the primeval waters – a symbol metaphysically meaningful: “and then they [the four gods] made the water and created in it a great fish similar to an alligator which they named Cipactli, and from this fish they made the earth as shall be told […] Afterwards all the four gods, being united in work, they created from the fish Cipactli the earth, which they called Tlāltēuctli and represent as the god of the earth, extended over a fish as having been made of it.” Another account adds that its body was ripped in two by Quetzalcōātl and Tezcatlipōca to create the sky and the earth. However s/he remained alive and requested human blood as a repayment for its sacrifice. The reason for using “s/he” and “its” is that the sex of the deity is ambiguous: the name Tlāltēuctli meaning “Earth Lord” is normally masculine but s/he is often depicted with female clothes for instance or regarded as a goddess; we may consider her/him as dually sexed. The myth of Tlāltēuctli’s dissection remembers that of the Mesopotamian sea entity Tiamat, or that of Ýmir, the Norse primal giant killed by Óðinn and his brothers Vili and Vé to shape the earth from his flesh, the sky from his skull, etc. His name could be derived from the PIE root *yemH- “twin” and he was maybe a hermaphroditic being. Ýmir is cognate with Sanskrit Yama (“twin-born”), the first mortal to die and then becoming Lord of the Ancestors, and his twin sister Yamī, as well as with Avestan Yima, Old Persian Yama, ruler of the world in a golden age but eventually killed by being cut apart after sinning, and perhaps with Latin Remus, murdered by his twin brother Remulus, the founder of Rome.

[26] In addition to the German academic cited in our notes about “Death is a Spiral”, we can also mention the essay The Exaggerations of Human Sacrifice by Davíd Carrasco in The History of the Conquest of New Spain by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, edited and with an introduction by Davíd Carrasco.

[27] Excerpt from a song in Ancient Nahuatl Poetry, translated by Daniel G. Brinton.

[28] Quoted partially in Miguel León-Portilla, Aztec Thought and Culture, op.cit.

[29] Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Ātmayajña: Self-Sacrifice, published in The Door in the Sky, Coomaraswamy on Myth and Meaning, selected and with a preface by Rama P. Coomaraswamy.

[30] Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa as cited by A. K. Coomaraswamy, ibid. Elements, plants, animals and the products of cows like milk and butter, perhaps men in a very remote past, and so forth, were used in the Vedic sacrifice, as well as more recently in some Tantric rites and Kālī cults for instance. In case sacrifice is not internalized or symbolical, when living beings and not surrogate offerings or representations are offered, it is for them the opportunity to gain a posthumous promotion from the Vedic point of view. Besides, still according to the same perspective, sacrifice is for the good of the whole universe – itself born from the sacrifice of a primordial cosmic being in one Vedic cosmogony – and therefore “killing in a sacrifice is not killing” (Manusmṛiti). It is said in the Brāhmaṇa-s and the Manu’s Laws that the beings (including trees and grains for instance) not ritually killed or transformed by Vedic verses will take revenge on their murderers in the Otherworld. Our world is a gigantic slaughtering and even veganism implies the irreversible annihilation of other beings: death is necessary to sustain life. According to the Aztecs, it was lawful to repay earth – the ravaged body of Tlāltēuctli – by sacrifice for the sustenance provided to men; it was a fair exchange, a way to keep a right balance.

[31] Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return.

[32] Mircea Eliade, ibid. Of course, this applies to the rituals founded on a myth, an exemplary model, and that request the establishment of a consecrated space, although some sites are naturally “places of power” and constitute “the centre of the world” for the participants involved; a traditional city like Mēxihco-Tenōchtitlan can be built on an archetypal model, for example with a centre and four major avenues or quarters oriented more or less according to the cardinal points. Likewise for a land, like early Celtic Ireland symbolically divided into five provinces, with Mide (“middle”), created from portions of the four provinces meeting at one hill, being the centre according to Keating. The profane modern so-called “rituals” do not deserve this name in our view.

[33] Mircea Eliade, The Quest, History and Meaning in Religion.

[34] All citations from the Devī Gītā are taken from an anonymous English translation, published in 1910 in India. The last quote reflects a tendency in Hinduism to consider one god/dess, or their couple, as the highest deity, often identified with the First Principle or ultimate reality. The other gods are not “false” or demonized, but regarded as powers derived from the One (“This One becomes the All”; Ṛgveda Saṃhitā), possibly a biunity, an identity of two contrasted principles in the case of Śiva and Śakti. Ultimately, nirguṇa brahman (Brahman having no qualities, no attributes…) transcends all futile attempts to describe it: it is neti neti “neither this nor that”; but as saguṇa brahman (Brahman with qualities), it manifests itself as a multitude of worlds and beings, some gross, some subtle, including the divinities and their archenemies. For Coomaraswamy, the celestial gods deva-s defending the cosmic order and their opponents supporting chaos, the asura-s (A.K.C.’s rendering: Titans; Zimmer: anti-gods), generally considered malevolent although some of them early joined the deva-s, represent the powers of Light and Darkness; “although distinct and opposite in operation, [they] are in essence consubstantial, their distinction being a matter not of essence, but of orientation, revolution or transformation […]”, Angel and Titan: An Essay in Vedic Ontology, published in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Dec., 1935). It also exists in Hinduism other perspectives than henotheism such as hard polytheism.

[35] Devīmāhātmyam, part of the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa, English translation by Frederick Eden Pargiter.

[36] “Tlilan Tlalapan” in the book of Léon-Portilla. The duality of the black/red colours is similar to that of black/white: night and day, darkness and light… It is hard to know exactly the nature of Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcōātl: an account comments that he was named after the god, Quetzalcōātl being the theophoric element. The historical ruler may have been an embodiment of Quetzalcōātl, a culture hero or/and was able to become a divine being. Foundational myths and historical facts are greatly interwowed in the case of Quetzalcōātl.

[37] Snakes and birds may be associated with Quetzalcōātl, for his name is often translated from Nahuatl as “feathered serpent” or “quetzal-feathered serpent”; the resplendent quetzal is a bird famous for its beautiful feathers. The name of the god is also interpreted metaphorically by some scholars as “precious twin”.

[38] As cited by René Guénon in Man and his Becoming According to the Vedānta.